How biomechanics tracked by Semi-Automatic Offside Technology can be leveraged to innovate football analytics

Juan Vila Rodriguez

Table of Contents

- TLDR

- Introduction

- How to Use Musculoskeletal Data

- Precedent and Replicability Across Sports

- Limitations and Constraints

- Conclusions

TLDR

The world of football is currently going through what is essentially an arms race to see who can create the most innovative, advanced data analytics department. However, whilst clubs and firms alike are using event-level data and conventional GPS tracking, there is a new, underused data source yet to be properly harnessed.

Semi-Automated Offside Technology (SAOT) is rolling out across top competitions, using musculoskeletal tracking to track player’s movements across the pitch. These data points can power objective, scalable biomechanics for recruitment.

Extracting kinematic features of players, fusing it with event-level data and tracking models, football can replicate the success shown across other sports analytics departments, like with Luka Doncic’s arrival to stardom in the NBA in an undervalued draft-day trade.

There are some doubts to be casted regarding coverage heterogeneity across providers and competitions, as well as the legal ramifications regarding GDPR for the player’s biometric data, but the fact these systems are in use would suggest club and competition contracts alike cover this area already.

Early adopters can become the first to reap the benefits of how integrating objective biomechanical analysis can improve profiling decisions, capturing recruitment surplus before wider standardisation.

Navigate Table of Contents

Introduction

As someone who consumes endless amounts of football-related content, whether it be in text or video form, I have often come across various forms of player evaluations. As a personal preference, I generally like the analysis I consume – for me to at least consider it somewhat good – to be substantiated in data in one way or another.

Another form of analysis I have often come across is the analysis of body mechanics, whether it be in a player’s ability to accelerate and decelerate, their ball-striking etc.

This general methodology, however, is something I never lent much credence to, typically discarding it for its proneness to subjectivity and how it can be influenced by various biases (see Nobis & Lazaridou, 2022), so I usually saw this discussion around biomechanics as more of an unsubstantiated pseudoscience.

This made me think, however – how can this be turned into an actual science?

My curiosity was sparked when I saw a job listing which entailed researching new technologies, such as musculoskeletal tracking, in football. I began to think of semi-automated offside technology (SAOT), and the technology it uses, and how this could begin to solve the issue of a lack of scientific consistency behind the discussion of biomechanics.

With access to the musculoskeletal data used for SAOTs, one could model and track players bodies and be able to objectively evaluate and substantiate how different body positioning, structures, and compositions are able to affect outputs

Premier League

Navigate Table of Contents

How to Use Musculoskeletal Data

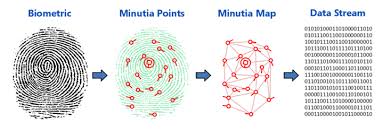

First, to understand how musculoskeletal tracking methods can be harnessed in football data analytics, we must first understand what the term refers to. Musculoskeletal is defined as ‘relating to the muscles and skeleton and including bones, joints, tendons, and muscles’ (Cambridge Dictionary).

Essentially, this is technology that tracks players bodies. How these datapoints are collected and implemented can vary across competitions, but the overall premise is the same.

There are various cameras across the stadium – for example, FIFA competitions have 12, the Premier League have 30 – which work at varying paces, although always at more frames per second / Hertz than usual broadcast cameras, tracking points on every player’s body which can then allow a 3D reconstruction of the field of play, the ball and all the players and their precise actions (FIFA & Premier League).

Within football, use of musculoskeletal knowledge has rarely been used in used in a context of player evaluation or recruitment. Instead, it has been used much more for sports-science and expanding knowledge on injury prevention (see Lemes et al., 2021), as well as creating 3D simulations of game simulations for match analysts to relay insights to coaching teams.

So, this technology being used in recruitment is virtually unparalleled, potentially opening the door for some very high returns on investment, as one can be the first to get their shoe in the door and innovate in this ever-expanding sector.

But, in this context, the question posed is: how can we use the body of a player to make better decisions about a player’s ability?

The first example I thought of, and the one which ultimately drew me to this topic, is that of the science behind ball-striking. This refers to the way in which the overall body of players is positioned when shooting the ball towards the goal.

In this context, if analysts were to work in tandem with physicists, biophysicist or biomechanists who would be able to, based on the data points available, model the human body and predict the flight of the ball based on certain key reference points of the shooter to the ball.

Comparison: Paqueta blasts in a goal from outside the box – Jackson falls and hits row Z

For example, the proximity of the shooter’s planted foot to the ball, the angle of their back’s inclination, the amount of swing on the shooting leg, how far the centre of their chest is from the ball, etc.

Then, meshing this physiological modelling with event-level data which, using the more conventional geo-tracking systems currently deployed, can track where a ball is shot from, who shoots it, how they shoot it, and where the shot goes, analysts can compare various xG or post-shot xG models, applying an unprecedented factor of how the shooter’s body was aligned to further improve the model.

They can then use this information to compare players across teams and leagues. Creating these systems can then be used to identify players with particularly good ball striking who, as a hypothetical example, may not be scoring as much as one expected due to team environment, where either their team as a whole is not good enough to consistently provide chances for the player, or the player is being underutilised.

Another aspect for which musculoskeletal analysis could be used in football replacement could be in replacing the subjectivity and personal bias – of which there is an extensive history of in football (see Nobis & Lazaridou, 2022) – when it comes to conventional forms of scouting.

For example, when analysing a winger, you can analyse body language by literally looking at the physical changes in their body before and after a successful or unsuccessful attacking attempt.

Conventional scouting reports may come to a consensus that a player may have a poor personality, often showing to be too easily defeated, but these reports are also subject to personal bias and could be swayed by preconceived notions.

However, after analysing the musculoskeletal frame of the player’s body throughout a game, and you find that they are, in fact, less likely to literally ‘drop their head’ after unsuccessful actions, you could find yourself an underpriced player which could provide greater marginal returns on your investment were you to sign them.

SportsBible

Navigate Table of Contents

Precedent and Replicability Across Sports

Football is a sport notorious for lagging behind others in terms of the level of advancement in analytics.

Unlike other more tried-and-tested uses of musculoskeletal analytics in footballs, like in sports-science, there is not much infrastructure or guidance to create an effective analytics pipeline in football. Therefore, there’s a certain risk one could incur were they to be the first to try leverage this technology.

As with any higher risk reward investment, it could come at the cost of hefty sunk costs after a costly process of implementing such extensive infrastructure.

To ease nerves, however, one can look at how the use of this tracking has worked in other sports which tend to act before football.

Perhaps the most high-profile use of musculoskeletal analysis can be seen in Luka Doncic’s arrival to the NBA. At first, he was a third-choice pick for the Atlanta Hawks before being traded on draft-day to the Dallas Mavericks, where he began his rise to NBA stardom.

This, however, would not have been possible were it not for the use of biomechanical analysis of Doncic’s actions back in Europe. A vast majority of NBA team’s scouting reports for Doncic raised significant doubts over his athleticism, and whether he would be able to properly adapt to the NBA.

The Mavericks, however, used motion capture systems to discover that, in fact, his athleticism was up there with some of the best in the league (SBJ). Using this analysis, they were able to circumvent one of the primary concerns with visual scouting – subjectivity and biases – to make an undervalued trade which gave them much greater returns.

ESPN on YouTube

Baseball is another sport long renowned for its pioneering of sports analytics, and the use of musculoskeletal tracking has been around since as early as 2015, when the Tampa Bay Rays were the first team in the MLB to implement biomechanical tracking cameras in their stadium.

Joshua Kalk, a physicist by trade, developed various systems in the early 2010s using tracking cameras which could capture movements from pitchers and hitters, primary to assess injury risk by tracking player load (DRB).

This same data can also be used to analyse the biomechanics of players, creating the opportunity to create longitudinal data to track a player’s movements and progress over time, helping to evaluate players over time and inform scouting and, finally, recruitment decisions.

KineTrax

Another example of the use of these biometrics into player evaluation is the NHL Drafting Process. As part of the medical, prospective players undergo rigorous physical testing – all recorded and tracked with a wide range of devices designed to measure the athlete’s physical qualities.

From portable height measuring machines to 3D camera systems that track different part of the athlete’s body mechanics in exercises like their horizontal jump, a comprehensive physical profile is created on all draft prospects (NHL).

This information can then be used to evaluate injury risk, much like in the current use of musculoskeletal knowledge in football, and can also be used to provide predictive information on performance.

NHL

Navigate Table of Contents

Limitations and Constraints

Potentially the greatest issue which could be encountered with incorporating musculoskeletal data and analysis into to the player evaluation process would be the lack of wide-spread implementation across the world of football.

In baseball, for example, not only do all MLB teams have kinetic tracking cameras, but so do the NCAA teams (college teams, virtually acting as feeders for the MLB). The world of football, however, simply does not have this level of infrastructure or accessibility to tracking, and it’s still very much concentrated in the ‘top’ competitions.

For example, the earliest mainstream attention this technology received was due to its use for Semi-Automated Offside Technology (SAOT) in the 2022 FIFA World Cup, where it received great praise for its swift acceleration of VAR reviews.

Besides that, it’s currently used in the Champions League; the English Premier League and Championship; the SPFL; the Bundesliga 1. & 2.; the Serie A; LaLiga; Liga BBVA MX and CONMEBOL Libertadores amongst others.

FIFA

This type of scarcity can create a limitation in terms of the scouting range for which you can apply these methods. If you were to start using these tools in recruitment analysis to seek out under-valued players in more discrete leagues which would be able to scale to other leagues (much like the example of Luka Doncic), this would simply be impossible due to there not being any availability of data to analyse.

But, with more leagues seemingly willing to incorporate SAOT to improve their VAR process, this means that musculoskeletal tracking will inevitably be available across more leagues, increasing the availability and range of the practical uses for the tracking systems.

Something to look out for could be an expansion on UEFA’s side which would see SAOT in the Europa and Conference Leagues, potentially proving to be gold mines for recruitment in a hopefully not too distant future.

Amazon Prime Video Sport on YouTube

Another issue is the fact there is not perfect linearity in the methodology behind the collection of this data across competitions.

Whilst a few leagues and competitions use the same provider or technology, like the English and Scottish divisions using Genius Sports (LawInSport), there is not necessarily a gold standard between different providers.

For example, for SAOTs in the 2022 World Cup, a sensor was used in the ball to send data to the video operation room 500 times per second, allowing for a much more precise detection of the kicking point. In the Premier League, there is no sensor in the ball for SAOTs, instead relying on the accuracy of the cameras around the stadium to accurately determine the precise moment the ball is kicked (FIFA & Premier League).

This highlights an issue, albeit arguably a relatively small one given the robustness of the technology around it, for external validity when being able to extrapolate findings from some leagues to others. The problem is like, for example, if progressive passes are measured different in X and Y league, it would be difficult to accurately see which players would be able to scale between leagues if data collection is different.

Barca Innovation Hub

There could also be a legal can of worms to be opened regarding the rights to this data.

There have already been legal challenges made on the legitimacy and legality of tracking player data, with over 400 pro players bringing legal action against organisations and companies that use footballer’s data and personal statistics.

The legality of gathering this data and using it to analyse their movements and body mechanics, may be dubious given how this is probably protected under General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the EU and the UK as it would be considered biometric and/or health data (Sports Law & Taxation).

ZKTeco

However, if this data is being used for broadcast in international and national competitions for semi-auto offsides, it would be fair to assume that, within player’s contracts, there are clauses in which they give permission for the collection and use of such data, either on the club or the competition’s side.

For full legality, the consent must be clear and explicit, although one on the outside would assume that clubs and leagues would make sure this is the case to cover themselves were there to be further complaints raised (see Hill & Rhodes, 2023).

Navigate Table of Contents

Conclusions

The concept of using musculoskeletal data or knowledge by itself is certainly not novel to football. The future of musculoskeletal technology in football, however, is extremely bright.

By turning body-motion data into clear recruitment signals, operationalising their biomechanics as model features, lining them up with event-level data, one can become the front-runner in innovating football analytics.

The precedent set across other sports – like how Luka Doncic, one of the best players in the NBA, was an undervalued draft-day trade thanks to musculoskeletal analysis indicating he had greater athleticism than scouting reports suggested – indicate positive feasibility and upside if a similar investment were to be made into football.

Some concerns are to be had regarding the legality of tracking and analysing these kinematic features, particularly within the EU, and wider implementation. However, as more leagues improve the functionality of their VAR by adding Semi-Automated Offside Technology, the availability of musculoskeletal tracking will only continue to increase, further enhancing the breadth of this type of analysis.

All in all, an effective process consisting of accurate modelling through collaboration between physicists and data scientists, as seen in the MLB, and accurate modelling can offer a practical route to secure early-mover advantages in football recruitment.

Leave a comment